A

Difficult Formula: Math = Fun

At Williams College, even calculus is cool

by Daniel McGinn

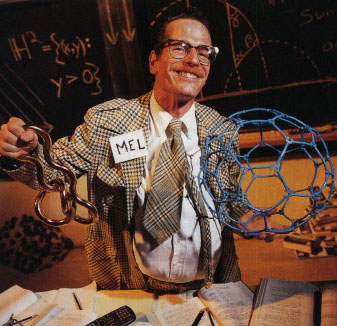

Adams plays a used-car salesman in some classes

| (Taken from Newsweek, June 5, 2000, pg. 61) | ||

|

A

Difficult Formula: Math = Fun

|

|

|

| Would

you take math from this man? Adams plays a used-car salesman in some classes |

||

|

This is math? It is at Williams College. "We do whatever it takes to get the biggest audience possible," says department chair Colin Adams. And it's working. Next week the elite liberal-arts school in Massachusetts will graduate a record 42 students with bachelor's degrees in mathematics. That's 8 percent of the class--at a time when just 1 or 2 percent of students nationally choose math as a major. Even at Williams math can't compete with the hottest major, economics. But the subject has earned a respectable buzz, which may offer larger lessons for educators clinched in a national debate over math. The issues are complex but boil down to one thing: how to excite kids about math? At Williams the answer is fun, imaginative teaching. In the '70s and '80s, Williams's math department was like that of most schools: arrogant and uncompromising. "The sense was that math ought to be hard, and only the best and brightest students should be taking it," says Olga Beaver, who joined the faculty in 1979. So tough introductory classes acted as filters, causing many students to find a different major. But in the late '80s a new generation of faculty arrived and made intro classes less intimidating. They developed courses that would appeal to nonmajors, like math for finance and math for medicine. In classrooms, teachers began assigning more group projects to combat the image of math as a solitary pursuit. The bigger changes came as the

department focused on hiring great teachers, regardless of their research

specialty. Two of Williams's 12 math professors have been named the country's

best collegiate math teacher in recent years; Berger is a finalist this

year. In 1995 William swiped a star statistics professor from Princeton;

now 40 percent of Williams undergrads take stats. Make no mistake: the

school is still teaching tough material. In differential geometry one

morning, Frank Morgan fills white boards with incomprehensible stuff.

(Sorry professor: you lost NEWSWEEK at "hello.") But

to make it accessible he describes the history behind the theories, from

Kepler to Newton to Einstein. Later Morgan takes a seat among the student

and stares at the board with them. "Don't be scared," he says.

"Just enjoy watching how complicated it is. Students have learned to find beauty in that complexity. Sitting around the library, five students recall Tom Garrity teaching an entire class while hopping on one foot, just to keep kids interested. But they also remember struggling through marathon take-home exams and burning through erasers long past midnight. Most intended to major in something else, but were wooed by personable professors who teased them with challenges. After graduation a few will become mathematicians, but most will take jobs in finance, computers or a host of other fields. But Shara Pilch, who graduates with a math degree next week, intends to use this equation on younger students. "When I do a math problem, I can feel my neurons grow," she enthuses. Pilch will begin firing neurons as a high-school teacher in Webb, Miss., next fall.

|

||